“follow him”—the poem Jenny Zhang published in Buzzfeed that kinda made it sound like she had been sexually harassed by “@PissPigGranddad” back in August 2017.

This poem describes the libidinal conflict between the so-called “dirtbag left” and the “left-liberal identitarians” as it could have been understood precisely at that point in time—the “ambient irony” of the discourse that has shifted ever so subtly (but unmistakably) since that particular period in the immediate aftermath of The Trump Election. It is about desiring-recognition among the hip crowd of extremely online people, the recognition of niche internet celebrities—not the real celebs, but those known among the urban coastal left-wing millennials, the people, the virtual people, who produce the ideas of this generation’s cutting edge cultural content, whatever that is and whatever that may be. The title: “follow him”—is that a command?—we know this is about a recognition mediated by followers, by fans, a relation not between two immediate individuals but between two brands passing each other like ships in the turbulent waters of public opinion.

Noteworthy about this poem is that it comes from a remarkably mainstream literary voice. To talk about this poem is not to try a critical exegesis of dril tweets or the Elliot Rodger manifesto, where one must explain beyond any doubt why the “outsider text” should be treated “as a form of literature.” Right at the top of Zhang’s personal website: “WINNER of the Pen/Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction WINNER of L.A. Times Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction FINALIST for NYPL Young Lions Fiction Award FINALIST for Brooklyn Public Library Literary Prize FINALIST for The Believer Book Award NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY The New Yorker • NPR • O: The Oprah Magazine • The Guardian • Esquire • New York • BuzzFeed • New York Magazine • Nylon”. Here we are dealing with capital-L Literature that is already recognized as such. This is what comes out of the Iowa Writers Workshop. This is the literature of the establishment, of the culture industry. Somehow this feels almost anachronistic to me, as if we (and by “we” I mean the people I presume will read this blog) have already wordlessly agreed that the contemporary literary avant-garde, or at least the stuff that is worthy of discussion, is occurring in the fragmented, marginal, liminal spaces of tweets, blogs, and shooter manifestos rather than the literary magazines, webmags, and so on. I think this tension animates this poem… but in the opposite direction.

“follow him” is about the relationship the speaker has with a dirtbag leftist: “I dated a white anarchist / who made me do all the dishes / while he crowdfunded his trip to Rojava”. This no doubt refers to Brace Belden, “an American leftist who volunteered to fight with the People’s Protection Units (YPG), a Kurdish militia, in the Syrian Civil War. Belden is also widely known as his former Twitter handle, PissPigGranddad” (Courtesy of Wikipedia—both Belden and Zhang are immortalized with their own Wikipedia articles. Not the case for any of the individual “Chapo Trap House” hosts…). Excerpts from Belden’s tweets as “@PissPigGranddad” are included: “war changes u… / two weeks ago I was an idealist… / now all I desire is Wi-Fi good enough / for 30 seconds of Bang Bus”. The reader might even be led to think that the poem tells a nonfiction account of a relationship between the real people Zhang and Belden—these scenes, the literary come-up micro-celebs and the radical activist micro-celebs, seem so incestuous that it could be plausible, especially considering the emergence of a new genre of “call-out literature” that exposes the misdeeds of someone with a modicum of internet fame, a call for their followers to renounce their misguided following, a call for cancellation and exile—but the two have apparently never met.

So never mind that it is a fiction: in this poem we have the idea of the author (the speaker) and the idea of dirtbag leftist Brace Belden. “I know this type better than I know / myself* all the world’s tragedies / a stage to put his ideals into action*”. And so let’s leave Belden behind and simply call his shadow “The Dirtbag”—the Speaker knows the Dirtbag better than she knows herself. She doesn’t know herself, the Dirtbag prevents her from knowing herself. She only knows herself inasmuch as she is the object of the Dirtbag’s fleeting desires, which aren’t directed at her so much as the virtual world of his lofty revolutionary ideals, of video games, and of Twitter and Tumblr and Reddit. “now all I desire is Wi-Fi good enough / for 30 seconds of Bang Bus”. The Dirtbag is a composite of all the men she’s dated, an obscene cubist bricolage of a man, a fucker, a mediocre white man, whose dick-gun swagger obscures his inescapable white fragility, a fragility of which he is frustratingly unaware.

In the course of the poem, the Speaker dates the Dirtbag, he leaves for Syria where he enjoys the recognition of online celebrity, and he returns, ungrateful as ever, to her motherly dinner table.

in yr best light you were still

extremely wasteful: smeared yr secretions

everywhere & showed parts of you

nonconsensually: are you still

trying to get people to talk about you?

will you sleep over in this economy?

i will smash anything with you

long as i am correctly quoted:

“rn my life is v nicely 2/3 marxism-

leninism & the living struggle

& 1/3 reading my horoscope at 2am,

thinking about my love life”

there’s plenty that can’t be said

& yes yes I know visibility is a trap

yes yes I know everyone here

is vibrating through some truly ugly notes

yes yes ok yup I have never uttered a thought

to someone who hadn’t already thought it:

yes sure it is easiest to mock the sincere:

war is corny & revolution threatens

irony, still I want my soft sockets

touched & refuse to give birth

heartlessly: I won’t budge on wanting love:

human touch: not everything

has to be profitable

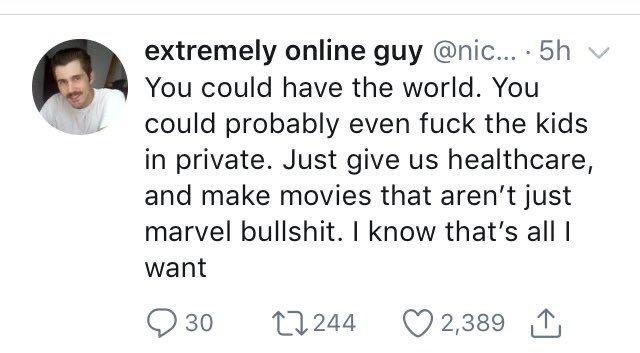

The first stanza of the poem the Speaker addresses the Dirtbag in the tone of the call-out post before turning into a defense of the Speaker’s tendency toward sincerity and softness. The Dirtbag is a grotesque exhibitionist: “in yr best light you were still / extremely wasteful: smeared yr secretions / everywhere & showed parts of you / nonconsensually: are you still / trying to get people to talk about you?” He is a pervert; in exposing himself he brings shame to the other. And in exposing himself he makes it so that he is talked about, he builds an audience. He exposes himself “nonconsensually” but the consent is retroactively constructed through the affirmation of the audience, of the fans, and through his ironic distance from his own exhibitionism. It is his irony that makes it difficult for the Speaker to speak of him: “there’s plenty that can’t be said / & yes yes I know visibility is a trap”. The Speaker by contrast embraces sincerity, softness, physical affection, even though it makes her vulnerable to mockery: “yes sure it is easiest to mock the sincere: / war is corny & revolution threatens / irony, still I want my soft sockets / touched & refuse to give birth / heartlessly: I won’t budge on wanting love: / human touch: not everything / has to be profitable”. War and revolution are identified with sincerity—wars are the works of the dead-serious; the urgent nakedness of desire in the revolutionary moment leaves no room for cynical ambiguity. You can mock the sincerity of war, but still I want the sincerity of love.

“open letter to my facebook friends

who voted for Jill Stein:

unfriend me now, I don’t care

if we’ve known each other for ten years!

delete me from your friend list!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!”

at this point my life is very nicely

2/3 wishing I were dead and 1/3

wishing I was never born

tbh your problems won’t go away

just bc you finally acknowledged yr own

longstanding depression:

the survivor mentality never worked

for me but then again I haven’t lived

thru much: “it happened to me:

I dated a white anarchist

who made me do all the dishes

while he crowdfunded his trip to Rojava”

Sincerity means your vote matters. The manic sincerity of the “open letter to my facebook friends” and the image of the impenetrable irony of the Dirtbag who “crowdfunded his trip to Rojava”. (The real Belden did not crowdfund his trip.) Both are mediated by the relationship to followers on different internet platforms, both are demands for recognition beyond the simple “like/favorite/heart”—either sever the relationship entirely or send me money! The Speaker’s frantic demand for the Jill Stein voters to unfriend her is connected to the now-no-longer-repressed trauma of her relationship with the Dirtbag, who obscenely courts the recognition of his online following as he enjoys fruits of the thankless domestic labor of the Speaker. The Dirtbag strives for a virtual point of sincerity, to represent to his followers the lofty ideals of the people’s struggle, even as his existence is characterized by the contradiction of those ideals with his thoughtlessly violent heteropatriarchal position in the romantic relationship.

sigh:: another white boy fight club:

all the world’s pain is not enough raw material

for them to feel something:

“it’s actually insanely good to hurt bad people”

what’s the difference between looking for a bar fight

& looking for someone to liberate

after reading about Democratic Confederalism?

I’m not sure but the first dood overdosed

after getting into the Whitney

the second guy got clean and found someone

to profile him:: sigh:: these bros

would sooner tape their own suicide

than fail to leave a legacy

no man has ever been remembered

for doing what their mothers did

for them: feeding the hungry

without credit: “war changes u…

two weeks ago I was an idealist…

now all I desire is Wi-FI good enough

for 30 seconds of Bang Bus”

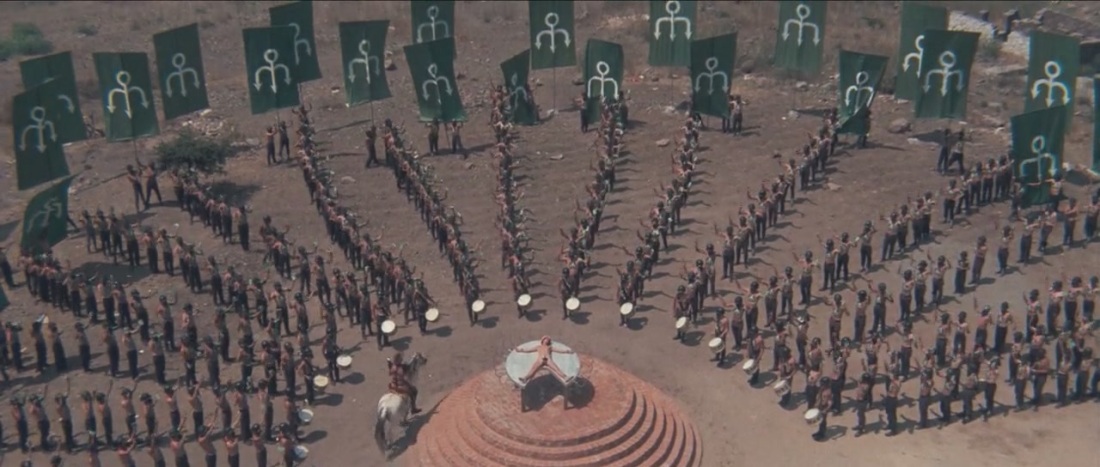

Rojava—sigh, another white boy fight club. Just another outlet for these bros to feel something. The drive for death is the drive for recognition. But now there is another white boy fight club, and now there are two Dirtbags: a revolutionary and an artist, who overdosed after he got “into the Whitney”. The art world fight club and the revolutionary world fight club. Dead doods. Both sublimations of that white cis male fight urge. Both ways for these boys to leave legacies, both ways for them to avoid their mothers, their mothers that the Speaker speaks for. The thankless toil—no one will remember the women. No one remembers the devouring mother. All the Dirtbags desire are their virtual worlds, the legacies, the death in battle, the Gesamtkunstwerk, the Wi-Fi good enough for Bang Bus…

the socialist dream means Rolling Stone

will never write about the women

waiting at home: me and my friends can’t wait

to be a footnote* our whole lives condensed

into a line* it’s no wonder some lumpenproletariat

got so tired of browsing Tumblr

they joined the Kurdish militia*

there’s even an economy of Iraqi cabbies

who wait for white guys to land*

“I think I’m a famous leftist now”*

“did one of you make a wiki page for me”*

I know this type better than I know

myself* all the world’s tragedies

a stage to put his ideals into action*

all the pain in the universe raw material

for his Nihilist Pornography* Anarchist Puppet

Show* Camgirl Intifada* Neo Dadaist Vision of Hentai

Morphology* Tentacle Necronumen* Futanari Dentata***

“The socialist dream” is what obstructs the recognition of women in its demand for male heroes. The Speaker worries she will be only a footnote to the Dirtbag’s undeserved glory. The followers give the recognition. They make the wiki pages. The Speaker knows the Dirtbag better than she knows herself because she is subsumed into those followers, into the anonymous crowd, less than a footnote. The Dirtbag is lumpenproletariat, a drifter junkie, between two deaths, so he goes to Syria to die again, for good this time. The Speaker is Antigone, the woman between two deaths, “myself* all the world’s tragedies”, dying ignominiously and forgotten. The Speaker is indifferent to the façade of the socialist dream, or perhaps she is even hurt by it. She is not a socialist, because the socialist dream is the Dirtbag’s longing for heroic death, a longing that the market satisfies, Rolling Stone magazine, an economy of Iraqi cabbies, all actors on the world stage to put his ideals into action, all the pain in the universe the raw material for the socialist dream, all the horrific pornography that mocks the tender sincerity of the woman.

Fanservice: no matter what is happening

no matter who is mourning no matter where

the droughts may be no matter which island

is being slowly submerged underwater

no matter which union leader was assassinated

in broad daylight no matter which community

has come together to mourn the endless dead

he still manages to make it about himself

he’s into YPG women

who carry rifles by their butts

in his RPG past he killed a lot of strippers

he’s one of the rare few

who have come back

~virtually~

~*untouched*~

the innocent slain needs him alive

the army needs him alive

the unnamed dead need him alive

the Reddit users need him alive

everywhere he goes a Kurdish fighter

steps first

denying him the right

to fear anything

he came all the way to Syria

to care about something

for *once*

and still the wretched of the world

bend over backwards

to die before him

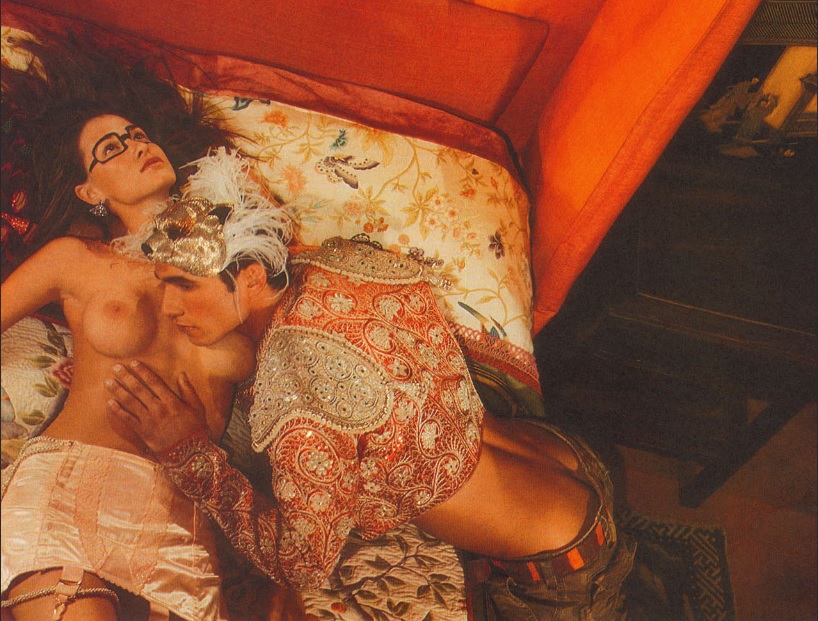

Fanservice. The Dirtbag is denied death because he is too valuable to his fans, and his fans are too valuable to the cause. The socialist dream. His RPG past is Grand Theft Auto, his virtual past and his virtual present, both shot through with violence against women, anonymous women, footnotes in history. Virtually untouched. The Dirtbag is too important to the Speaker, who hate-follows his Twitter. And Reddit needs him alive, Reddit, that hive of (cis, white, male) geeks. The Speaker wishes that the Dirtbag died—but then his death would make him immortal, so she is confused. White privilege, fearless white privilege immortalizes the Dirtbag as superhuman. He is a conquistador that plays the indigenous tribes against each other before proclaiming himself right hand of the king. But he is a superhuman idiot. He came to Syria to feel something for once, and now is denied even this. The Dirtbag would be incapable of sincerity even if he sincerely wanted it. His whiteness is beyond himself, and any action he takes is shot through with the irony of inauthenticity.

what’s it like to have so many people

invested in your existence?

those of us who knew him in NY & SF

are stuck archiving footage of him snorting

ketamine with neo Marxists who don’t like it

when you critique their anti-capitalist critique

of prostitution within the framework of

shameless anti-feminist-settler-colonialism—

I mean, okay… no one likes to hear that!

the real struggle as defined by an ex-junkie

beta male missing a core…

I thought literally everyone knew

fight club was really about brad pitt

desiring edward norton… like these two men

burned so much for each other

they had to keep making excuses to touch…

it’s absolutely true some white guys

would rather fight ISIS…

than be called a racist online!

anyone else nodding like yup yup yup yup?

anyone else vomited in daddy’s lap

and forgot to share it with their fans?

The Speaker is the librarian of the triumphs of the Dirtbag. She archives the footage of his drug use and she memorializes him in poetry. The Dirtbag and his dirtbag friends are sex-negative feminists. The Speaker, by contrast, stands defiantly for the sex workers in the margins, against the shameless anti-feminist-settler-colonialism of the Dirtbag, the shameless socialist dream. Shameless neo Marxists. But, she reflects on herself—no one wants to hear her critique of the critique. The Speaker watches the revolution going on outside from the balcony of her high-end brothel. The Dirtbag is sex-negative. Why? The Dirtbag is gay, he’s a repressed faggot. Mask off: Fight Club is gay. Can’t you see? That’s irony. Fight Club is beta males repressing the truth of how they are beta males. Ironic. Men fight because they want an excuse to touch each other, and because they need to sublimate the anger from being called racist online. Irony! That’s why the Dirtbag isn’t interested in the Speaker. Dirtbag Orpheus. Fanservice. Giving and receiving. Dead doods diddling. Sharing vomit with the fans. Perverts. A junkie nodding off. Anyone else nodding? The Speaker turns to her fans—yup yup yup yup. The Dirtbag has bad politics. Problematic. Perverse. Like and retweet.

you must really live for the state

of emergency: “we are here at home”:

I don’t think everything happens out there

on the streets: who u used to be vs

who u have become: carrying the banner

of any idea: reparations, restorative justice,

prison abolition: “I dwell in possibility”:

abandoning yr family to take up arms

somehow becomes beyond reproach:

so much is the opposite of glory;

that’s why the women in my family

tested the lowest for morality: 1973

was not good to us: cancer in your 12th house

means your “secret sorrow” is hot + buried

but what passes as flirtation online

doesn’t work analog: the same white guy

whose facebook posts I screenshot

lectures me on how my people really lived

under Mao: “did you actually fall

for that rightest propaganda?” I don’t know

exactly but I know I don’t wanna drive across town

to barter ingredients for your cruelty-free dinner

The ballad of the white Maoist and the diaspora girl. The Dirtbag lives for emergency, he lives to die, which is to not die. He is a Maoist because the wretched of the earth throw themselves to their deaths for his jouissance. The Dirtbag and his fans can’t let a diaspora girl play Marianne because they’re a bunch of racist faggots. Dwelling in possibility and leaving the girls at home. Beyond reproach, the Speaker is silenced by the cries of the fans, the rabble. Even if she wanted to—she can’t make her way across town to barter ingredients for the cruelty-free dinner because the fans are in the way, in the streets, carrying the banner for any idea, spewing vulgarities. The path between irony and sincerity is clogged. Where are their mothers? The Speaker is their mother. They can’t appreciate everything she’s done for them. All the thankless toil. They won’t let the Dirtbag die. They won’t let her smother him.

okay maybe I am consumed by rage

and inflict it on the people around me!

but I swear his beliefs are genuinely suspect

why is it always around dinner-time

that his interest in the no-work movement kicks in?

“you only work as much as is needed—no one

is coerced!” suddenly the new world order

flashed before my eyes—my people naturally

(free of coercion!) took up cooking, serving,

& cleaning without complaint and your people

took to feasting with a clean conscience—

“all of this given voluntarily!

each one takes according to need!

offers according to want!”

well life is rich and wanting to be someone

is very different from worrying abt the mothers

of the world who have given birth to men

who literally cannot feel—

even in death

even in fame

even when we beg them

to worry about something

other than how

they might die

having done nothing

worth noting

Dinnertime with the devouring mother. Maybe you are consumed with rage. But maybe his beliefs are suspect. A woman’s place is in the kitchen and a man’s place is in the streets. Between two deaths. Between two mommies. The Dirtbag is torn between his Jenny Zhang mommy and his Anna Khachiyan mommy (he has no father figure). Chose the wrong mommy—voted for Jill Stein. Boys never want mommy girlfriends, even if it seems like they do. They’ll gaslight you and cheat on you and run off to become the symbol of the revolution. All Dirtbags have mommy issues. They say it ironically but in doing so they lie—because they are being sincere, for once. White boy’s mommy never made him do anything, because she thought he was such a perfect little sweetie who could do no wrong—and that’s why he grew up to become the Dirtbag. Mommy is a jealous goddess, she deserves more followers. Follow her. Stupid white boy can’t even read a fucking book, just a fucking stoner. Shh! Don’t be mean. Do that in the subtweets. Even when he’s a bum he’s appropriating indigenous cultures. He has no tradition. Never had to face adversity in his life. Shh! If you confront him he’ll feel cornered. Don’t coerce him. Let him feast with a clean conscience. Eat some real food made by a woman of color. My little conquistador. If you don’t die before you get old, my little sweetums, I’ll kill you myself. He never learned how to feel. Even when he dies he’ll never learn how to feel. Shh… shh… it’s okay. Don’t cry. You are nothing. Mommy is here…